Celeste Roberge: Women of the Gulf of Maine

It may be that the Women of the Gulf of Maine began germinating deep in my subconscious the minute I learned of the reproductive cycle of Fucus vesiculosus. On a research trip with Jessica Muhlin, a marine biologist, to the Downeast Institute in Beals, Maine, on October 4, 2014, I was stunned by the revelation that this intertidal seaweed species with the common name “bladder wrack”reproduces from separate male and female organisms that simultaneously release sperm and eggs into the ocean at slack high tide, under calm, sunny conditions, during a full moon. How much more romantic and specific can it get? Ships sailing above, microscopic sperm fertilizing eggs below.

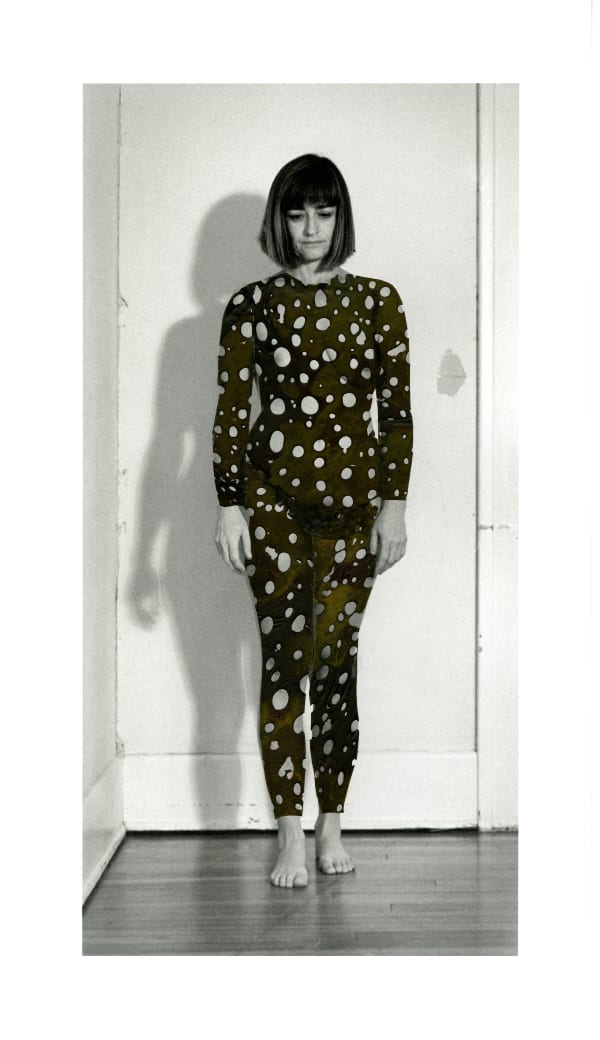

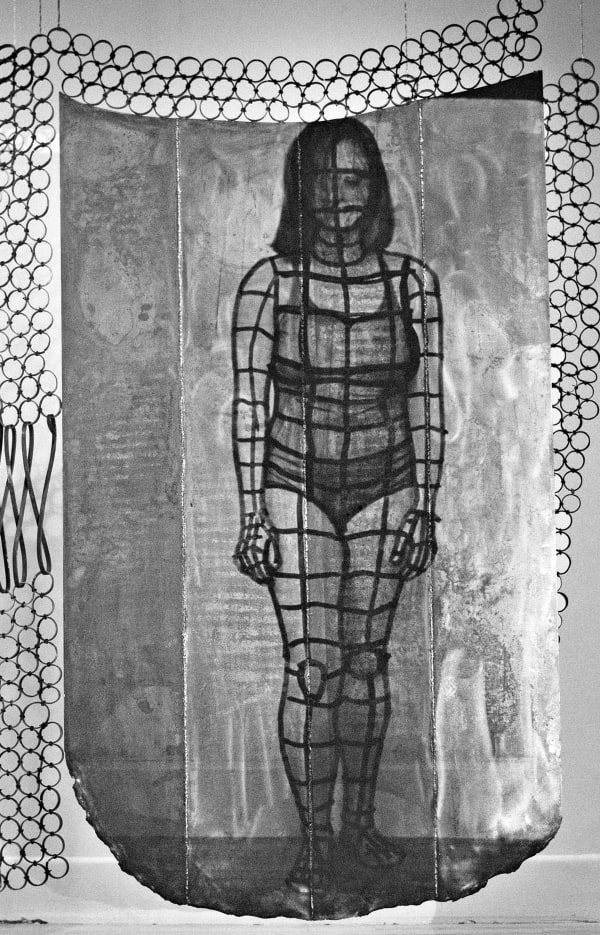

Women of the Gulf of Maine create themselves through the principle of self-organization, like much of nature. Each sculpture begins with one specimen of wet seaweed that is wrapped around a form. The figures emerge from the ever-changing morphology of the drying seaweed. No two seaweeds ever dry the same. I make decisions in the process: what is too dry, what is too wet, and what is just right. Added to the curling, curving, warping, and shrinking of the seaweeds as they dry is the material science of wax. Wax is liquid when hot, but it hardens very fast in the cold. How can I maintain the irregular hyperbolic curves and delicacy of seaweed, which is sometimes only one cell thick, while coating it with numerous layers of molten wax? There are drips, waves, puddles, and bubbles. From this primordial chaos, the figure emerges. Then I emphasize certain aspects, enlarging or diminishing forms and anatomical references—like suggestions of wings, head, or feet—or details of dress, like scarves, skirts, ruffles, and veils.

I speculate about the possible meanings of these creatures who appear in my studio, riding on their own slick and slippery wave. How to take something that is barely there—like a breath, a gust of wind, a wave, a splash, a touch, a feeling—and simultaneously make it seem like a female form? In their verticality, the Women of the Gulf of Maine are about presence, not seduction. Women standing. Women walking. Women waiting. These small figures are expressive of my desire to create new beings. There is the urge and the demiurge—the creator deity.

The Women of the Gulf of Maine are mythical, fantastic, surreal. They are not about beauty or the grotesque. They simply exist with all their differences. They are antique and archaic. Their forms combine elements from all the figurative sculptures that I have seen in a lifetime. They relate to worldwide traditions of statues of deities: Roman, Egyptian, Greek, pagan, prehistoric, Catholic, Buddhist, Hindu; the Apsaras, Korai, Caryatids of the Erechtheion; fertility goddesses, headless statues of goddesses in a colonnade. Every culture, every religion, over millennia.